I've been reading along slowly in Frost. The hallmark of my love of poetry is not that I see virtue in all poems or am in a constant state of swoon as I read them but rather that I'm willing to read so many that don't move me in the least in the search for ones I do enjoy. I'm bracing myself for a stretch of Frost poems that I expect will be an arduous journey. I'm at the end of selections from the first book and am headed into those of the second, nearly all of which are over 100 lines, many well over. I've never heard anyone tout Frosts long poems. Perhaps I'll be pleasantly surprised. Perhaps they're simply not known or widely read because their length makes them hard to anthologize. But I'm putting on my poetry parka and heavy books in fear of the worst.

The selections from A Boy's Will remained rather light and mostly dull. I enjoyed "A Tuft of Flowers" http://www.online-literature.com/frost/757/. I like the transformation of thinking in the poem from one of assumed isolation to assumed communion, and I like that the catalyst of such a transformation was a tuft of flowers unmowed, how it became a link between two people. And bravo that Frost accomplished the telling of this in rhymed couplets to emphasize the meaning.

I also enjoyed "A Line-storm Song" http://www.poemhunter.com/poem/a-line-storm-song/. It's a lovely love poem about ignoring the condition of the world and embracing anyway, reminding me much of one of my favorite love poems "Love is Enough" http://www.bartleby.com/101/801.html.

Thursday, November 13, 2008

Tuesday, November 11, 2008

To The Thawing Wind

As I mentioned, I enjoy poems of celebration and tribute. The next poem I enjoyed in the Frost collection was "To The Thawing Wind" www.internal.org/view_poem.phtml?poemID=155, which is also an invocation. I like the pace of it. He started with a couple of tetrameter lines but the rest of the poem has seven syllables per line. Each line is a command and begins with a heavy beat before falling into trimeter (this is the sort of thing I wouldn't normally notice without slowing down and wondering whether 7 syllables was a shortened tetrameter or an extended trimeter). I also like the end of the poem which expresses the poet's desire to be turned out of doors, to leave the insular, isolated life of desk and papers and engage the world. Whitman has a lines of that sort in "Passage to India," ending with "Have we not darken'd and dazed ourselves with books long enough?"

I agree that the ideal life involves both times of settled reflection and times of active engagement, mental vigor and physical vigor. It's a very hard balance to find when work often demands a great deal of sitting on our behinds in confined spaces. For Frost, at least during the times he's writing about in this period, weather dictated whether or not he was active, spring obviously being an invitation to go out. At present, here in Alabama, the cool fall weather does the same for me but work and the shorter days keeps me from enjoying it as much as I would otherwise.

One has to wonder what the most congenial vocation is for a poet. It's generally considered the academic life where their craft is considered a legitimate activity and where they can commune with other poets. Presumably, it also allows more time to practice one's art, though I know writer-academics who would dispute that. But it seems to me the academic lifestyle overemphasizes the contemplative aspects of life. Perhaps the poet, if teaching is to be his or her profession, would be better off teaching recreation. Or leave behind academia entirely, get a degree in finance or some other profession that allows you to make so much $ per hour that you only have to work 20 hrs per week and the rest of the time spend in pursuits invigorating to either mind or body in whatever ratio most benefits you. Frost's farming life is far from ideal since living by the demands of seasonal work creates extremes.

This strikes me as a serious issue that isn't given enough attention, this problem of how to create a life that is congenial to one's art. Academics tend to espouse academia or teaching of some kind but we all know there are more English majors and MFAs being unleashed on the world than there are positions for them to fill. The problem of a secondary profession needs to be brought up earlier to those with an economically self-destructive leaning toward poetry, a specialized career counseling. The best I've encountered so far is Carol Lloyd's Creating a Life Worth Living. But most people won't do the work in a book without the support of a leader or group. I encourage anyone with artistic leanings to get this book and go through it with another artist with the intention of continually using her approach to fine tune your direction in life until you've got something that works for you, your art, and your bank account.

I agree that the ideal life involves both times of settled reflection and times of active engagement, mental vigor and physical vigor. It's a very hard balance to find when work often demands a great deal of sitting on our behinds in confined spaces. For Frost, at least during the times he's writing about in this period, weather dictated whether or not he was active, spring obviously being an invitation to go out. At present, here in Alabama, the cool fall weather does the same for me but work and the shorter days keeps me from enjoying it as much as I would otherwise.

One has to wonder what the most congenial vocation is for a poet. It's generally considered the academic life where their craft is considered a legitimate activity and where they can commune with other poets. Presumably, it also allows more time to practice one's art, though I know writer-academics who would dispute that. But it seems to me the academic lifestyle overemphasizes the contemplative aspects of life. Perhaps the poet, if teaching is to be his or her profession, would be better off teaching recreation. Or leave behind academia entirely, get a degree in finance or some other profession that allows you to make so much $ per hour that you only have to work 20 hrs per week and the rest of the time spend in pursuits invigorating to either mind or body in whatever ratio most benefits you. Frost's farming life is far from ideal since living by the demands of seasonal work creates extremes.

This strikes me as a serious issue that isn't given enough attention, this problem of how to create a life that is congenial to one's art. Academics tend to espouse academia or teaching of some kind but we all know there are more English majors and MFAs being unleashed on the world than there are positions for them to fill. The problem of a secondary profession needs to be brought up earlier to those with an economically self-destructive leaning toward poetry, a specialized career counseling. The best I've encountered so far is Carol Lloyd's Creating a Life Worth Living. But most people won't do the work in a book without the support of a leader or group. I encourage anyone with artistic leanings to get this book and go through it with another artist with the intention of continually using her approach to fine tune your direction in life until you've got something that works for you, your art, and your bank account.

Friday, November 7, 2008

Culling

Over several months this past year, I went through a large pile (almost a ream) of photocopied poetry I'd collected over the years, culling almost all of it. I decided I would only keep those that were satisfying both in language and in meaning for me, or which affected me very strongly because of the use of language or the meaning. Much as I like the linguistic fireworks of Albert Goldbarth, I saved only one of his poems. In fact, it was reduced to a pretty thin pile which I've been typing into my computer so that I can ditch the paper copies. And reading over what was left, I realized I probably should have culled even more but left well enough alone.

It is with this new stricter standard in mind that I looked over selections I'd marked in the first 250 pages of the anthology of world poetry (which is a 1250 pg tome) and found much wanting. Quite a bit of what I marked amused me and much of it was out of sociological interest--I found it interesting and amusing that we shared such similar sentiments with ancient Romans.

By Martial:

You are a stool pigeon,

A slanderer, a pimp and

A cheat, a pederast and

A troublemaker. I can't

Understand, Vacerra, why

You don't have more money.

tranlated by Kenneth Rexroth

On a gentler note, from ancient India, by Prakrit:

Lone Buck

in the clearing

nearby doe

eyes him with such

longing

that there

in the trees the hunter

seeing his own girl

lets the bow drop

Translated by Andrew Schelling

But I find that what moves me the most both from among the poetry in my collected ream and from those circled in this volume are those of tribute or celebration, poetry with either a touch or a load of the ecstatic.

By Propertius:

O Best of All Nights, Return and Return Again

How she let her long hair down over her shoulders, making a love cave, around her face. Return and return again.

Translated by James Laughlin, this goes on to list other details of intimacy with that refrain.

And I like poems of artful and powerful clarity such as this one, also by the Indian Prakrit:

These women plunder my husband

as if he were plums

in the bowl of a blind man.

But I can see them, clear as a cobra.

Translated by David Ray

Anger and the drive to revenge is so palpable in that simple 5 line poem.

There are a few other curiousities and beauties but no time to share them and I feel it's best to end this review and move forward in the book.

It is with this new stricter standard in mind that I looked over selections I'd marked in the first 250 pages of the anthology of world poetry (which is a 1250 pg tome) and found much wanting. Quite a bit of what I marked amused me and much of it was out of sociological interest--I found it interesting and amusing that we shared such similar sentiments with ancient Romans.

By Martial:

You are a stool pigeon,

A slanderer, a pimp and

A cheat, a pederast and

A troublemaker. I can't

Understand, Vacerra, why

You don't have more money.

tranlated by Kenneth Rexroth

On a gentler note, from ancient India, by Prakrit:

Lone Buck

in the clearing

nearby doe

eyes him with such

longing

that there

in the trees the hunter

seeing his own girl

lets the bow drop

Translated by Andrew Schelling

But I find that what moves me the most both from among the poetry in my collected ream and from those circled in this volume are those of tribute or celebration, poetry with either a touch or a load of the ecstatic.

By Propertius:

O Best of All Nights, Return and Return Again

How she let her long hair down over her shoulders, making a love cave, around her face. Return and return again.

Translated by James Laughlin, this goes on to list other details of intimacy with that refrain.

And I like poems of artful and powerful clarity such as this one, also by the Indian Prakrit:

These women plunder my husband

as if he were plums

in the bowl of a blind man.

But I can see them, clear as a cobra.

Translated by David Ray

Anger and the drive to revenge is so palpable in that simple 5 line poem.

There are a few other curiousities and beauties but no time to share them and I feel it's best to end this review and move forward in the book.

Thursday, November 6, 2008

Nov 5, Beginning Frost

I've started with Frost at night instead of the morning. I was feeling the need for something grounded and stabilizing. I love the hardcover volume I found at a used bookstore for $4. Though it feels no older than 10-20 years, the copyright page gives no year beyond 1969, no reprintings. The book itself, with its embossed cover, feels stately. There is no introductory material beyond a photo of white-haired Frost sitting on a stacked-stone wall opposite the poem "The Pasture." The collection is arranged from earliest work to latest, starting with poems included in A Boy's Will (1913).

Although I enjoyed the meaning of the first poem presented, "Into My Own," I'm not taken by the music of any of the poems until I reach "Storm Fear." I paused at the end of this poem thinking it was free verse and ironic that I come to Frost's work for form and the first poem that strikes me as having beautiful music would be free verse. However, I was wrong. The poem might be considered a hybrid. It has no regular line length or meter. It can't be said to have a rhyme scheme but every line ending has a match somewhere in the 18 line poem, some of them 3 times. Alliteration and assonance occur frequently throughout, giving it much of its music. It could very well be that Frost eschewed regular form in the poem because it's about a frightening storm. The result is more pleasing to me than the strictly formal poems I'd read in the book to that point, which seemed stilted and include some of the common flaws forms are prone to: language twisted to get a rhyme at the end and adding junk lines (ones that in no way add to the movement or meaning of the poem) to get a rhyme ending.

So I came to the book wanting stability and between the hard stately covers end up favoring a poem about a storm that any formalist would consider discombobulated.

Although I enjoyed the meaning of the first poem presented, "Into My Own," I'm not taken by the music of any of the poems until I reach "Storm Fear." I paused at the end of this poem thinking it was free verse and ironic that I come to Frost's work for form and the first poem that strikes me as having beautiful music would be free verse. However, I was wrong. The poem might be considered a hybrid. It has no regular line length or meter. It can't be said to have a rhyme scheme but every line ending has a match somewhere in the 18 line poem, some of them 3 times. Alliteration and assonance occur frequently throughout, giving it much of its music. It could very well be that Frost eschewed regular form in the poem because it's about a frightening storm. The result is more pleasing to me than the strictly formal poems I'd read in the book to that point, which seemed stilted and include some of the common flaws forms are prone to: language twisted to get a rhyme at the end and adding junk lines (ones that in no way add to the movement or meaning of the poem) to get a rhyme ending.

So I came to the book wanting stability and between the hard stately covers end up favoring a poem about a storm that any formalist would consider discombobulated.

A Decision to Make

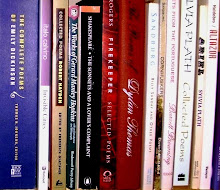

I have lots of books of poetry, so deciding which to devote my mornings to requires some thought. I've been easing toward this moment, though, and was able to pull four books from my shelf as possibilities: an anthology of world poetry from antiquity to the mid 20th century, and collections of Pablo Neruda, Richard Wilbur, and Robert Frost. The first I'd started on and had been enjoying when the whirlwind of rebuilding my life hit. Pablo Neruda is a much-lauded poet I'd read little of and been curious about. Richard Wilbur and Robert Frost both tend strongly toward formal rather than free verse poetry and I've been wanting to reconnect with form, especially blank verse, after spending nearly all of my adult life reading and writing free verse and enjoying the experimentation of the moderns. Perhaps my own slowing down makes dah dum dah dum dah dum more congenial to my spirit. Perhaps it's because in middle age I'm less concerned as a poet in expressing myself (in fact, I've arrived at a place where I feel I have nothing to say) and thus am freer to turn my mental energy toward better understanding and appreciating matters of form. What poetry has to say matters less to me now than it once did, so I'm less concerned that form be chosen to fit or allow the message. Also, it doesn't offend me to spend time writing in form for form's sake with nothing of import to say, or to read poetry whose virtue is largely in the execution of form. Of course, as always, the greatest pleasure is when one gets multiple fireworks of meaning and music.

Because translations are always mutations full of compromise, I decided against reading the anthology and Neruda at the same time. (Somewhere along the line, I decided to choose two books to alternate between.) I sided with the anthology because I'd enjoyed reading it so much earlier. It seemed there were surprises around every corner and the editors clearly had a sense of humor. Neruda will have to wait. Between my formalists, I sided with Frost. He seems a good place to get grounded before reading Wilbur, and Frost's frequent choice of rural subject matter appeals to me at the moment. Years ago, I read a collection of Frost and was surprised how little of his poetry I liked. I'm curious to see to see if that has changed.

So it will be poetry from around the world and through the ages, and Robert Frost to start with, in portions I won't try to predict.

Because translations are always mutations full of compromise, I decided against reading the anthology and Neruda at the same time. (Somewhere along the line, I decided to choose two books to alternate between.) I sided with the anthology because I'd enjoyed reading it so much earlier. It seemed there were surprises around every corner and the editors clearly had a sense of humor. Neruda will have to wait. Between my formalists, I sided with Frost. He seems a good place to get grounded before reading Wilbur, and Frost's frequent choice of rural subject matter appeals to me at the moment. Years ago, I read a collection of Frost and was surprised how little of his poetry I liked. I'm curious to see to see if that has changed.

So it will be poetry from around the world and through the ages, and Robert Frost to start with, in portions I won't try to predict.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)